The “Little Tramp” advertising campaign still stands as IBM’s most remembered one—and for all the right reasons. A collection of 1980s TV and print ads, designed to make IBM’s seminal lineup of personal computers more approachable, turned Charlie Chaplin’s most famous visage into the Big Blue’s de facto PC mascot. The Tramp was such an icon for IBM, its ad agency’s chairman had to explain why he wasn’t brought back for the successive campaign. The ad campaign is regularly remembered by professionals, analyzed by scholars, and would surely be recalled in just a few months due to the IBM PC’s 40-year anniversary.

The same can’t be said for IBM’s decision to take the OS/2, their advanced and technically demanding software product, and pay at least $1.5 million a year to share the naming rights with a second-rate, US-centric sports event. The IBM OS/2 Fiesta Bowl, as the event was formally called, united computing columnists and sports commentators in their bewilderment, especially as IBM was bleeding money and losing the a with Microsoft over desktop dominance. It does, however, show IBM’s bold attempt, however misguided, to market the OS/2 among people outside the company’s clientèle.

1990 was a rough year for the Fiesta Bowl. The college football competition, held in Phoenix metro area on a New Year’s Day, was put in a reputational disarray after Arizona voters initially declined adopt Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a paid state holiday. The same year, the bowl lost its first title sponsor, Sunkist Growers, as the citrus cooperative had to recover from a crop-ruining freeze. IBM’s fortunes weren’t great either: the company’s success with the original PC and its successors, the XT and the AT, did not translate into retaining control of the market. One of initiatives which the IBM was trying to build itself back with was the OS/2, a prospective replacement for Microsoft’s technologically limited MS-DOS operating system. IBM and Microsoft originally worked on the OS/2 together, but as the latter was finding its own success with graphical interface of Windows, IBM shouldered the responsibility for the former joint project.

IBM’s arrival as the corporate underwriter for the Fiesta Bowl was announced in December 1992. The deal let the embattled Fiesta Bowl stay in the top league of college football bowls, as IBM’s funds allowed it to hit the $6 million payout goal required by the Bowl Coalition. The three-year Fiesta Bowl sponsorship cost IBM $4.5 million total, according to the International Events Group data quoted by the USA Today. (Another reported figure is $8 million, as stated by a Creamer Dickson Basford employee in Marketing Computers.)

Whatever was the benefit for IBM, it wasn’t as straightforward as a pile of cash—and the company would have benefited from that. The deal was announced amid a series of layoffs, unprecedented for the company which prided itself on a policy of lifetime employment. Billions of dollars were written off to cover befefits for many IBMers as it forced them to retire. The company reported a 1991 annual loss of $2.86 billion, followed by a record $4.97 billion loss in 1992.

IBM representatives defended the deal vigorously. “It would be inappropriate to link one set of business activities with another,” said James C. Reilly, IBM’s US general manager of communications, as he was confronted by the New York Times about the sensibility of cutting jobs and doing high-profile sponsorships at the same time. In another statement, which makes less sense each time you re-read it, IBM press officer Rob Crawley told Open Systems Today that “you need mindshare of the market in order to do better in your market.”

Aside from an assortment of merchandise which pops on eBay to this day, the deal netted the right for IBM to advertise the OS/2 during the bowl as it was broadcast by NBC. A set of “Stay 2’ned for more” ads, which allegedly aired during the first IBM-sponsored Fiesta Bowl, tried to woo the audience with a screen recording of a 32-bit Lotus SmartSuite—whatever that meant for the uninitiated—and such zingers as “why not drag-and-drop yourself out to get it?” The 1994 set, per a short note in the IBM-backed OS/2 Professional, was devoid of computer jargon and more focused on people and activities.

Off the record, IBMers were not impressed with the endeavor. “It should have been called the IBM Bowl,” said an unnamed former IBM employee to Business Marketing in 1994, implying that the name-in-title schema, as opposed to the name-as-title one, did not make people link the competition with its sponsor. Rick Chapman, a former consultant for IBM and an author of In Search of Stupidity: Over 20 Years of High-Tech Marketing, wrote in his book that the sponsorship was known internally as “The Fiasco Bowl.”

Some sports commentators, noting how ridiculous bowl names were becoming, picked the Fiesta Bowl as their object of ridicule. “I am in awe of the IBM OS/2 Fiesta Bowl because I have absolutely no idea what an OS/2 is. For that matter, I have no idea what the OS/1 was,” wrote famed journalist Tony Kornheiser in his December 1993 column for the Washington Post. (Bowl names have evidently become even crazier, giving a fertile soil to many listicles.)

Save for the Arizona Wildcats’s historical shutout loss in the 1994 game, the OS/2 era was relatively uneventful for the Fiesta Bowl. At the same time, IBM underwent a corporate shakeup which set a new course for the company. John Akers, a lifelong IBMer who led the company as it was losing control over the personal computer market, was ousted in a management coup, with Lou Gerstner becoming the new CEO in April 1993. Under Gerstner, IBM hit the brakes on the plan, set in motion by Akers, to split the company into several independent units; cut ties with 40 ad accounts in favor of a consolidated deal; and, crucially, shut down the OS/2 project.

In September 1993, Bob Hunt, the Fiesta Bowl president, accused the IBM party of abandoning a new six-year, $20-million agreement ostensibly backed with letters of intent, says a note in Arizona Republic. The last Fiesta Bowl under the OS/2 banner was held on January 2, 1995, after IBM introduced a new major version of the system to compete with Microsoft’s upcoming Windows 95.

Hunt told that IBM decided to “get out of the sports marketing business,” which didn’t turn out to be that unequivocal. In 1996, for instance, IBM was a title sponsor for an Olympic gymnastics test event in Atlanta, and it continues to sponsor some major competitions to this day—like the upcoming US Open tennis tournament. It did, however, pull out of of sponsoring the Olympic Games in 1998, ending their 40-year partnership with a Sydney 2000 presence. IBM and the International Olympic Committee parted ways with public disagreements over cost sharing and Olympics.com web rights, the Wall Street Journal reported.

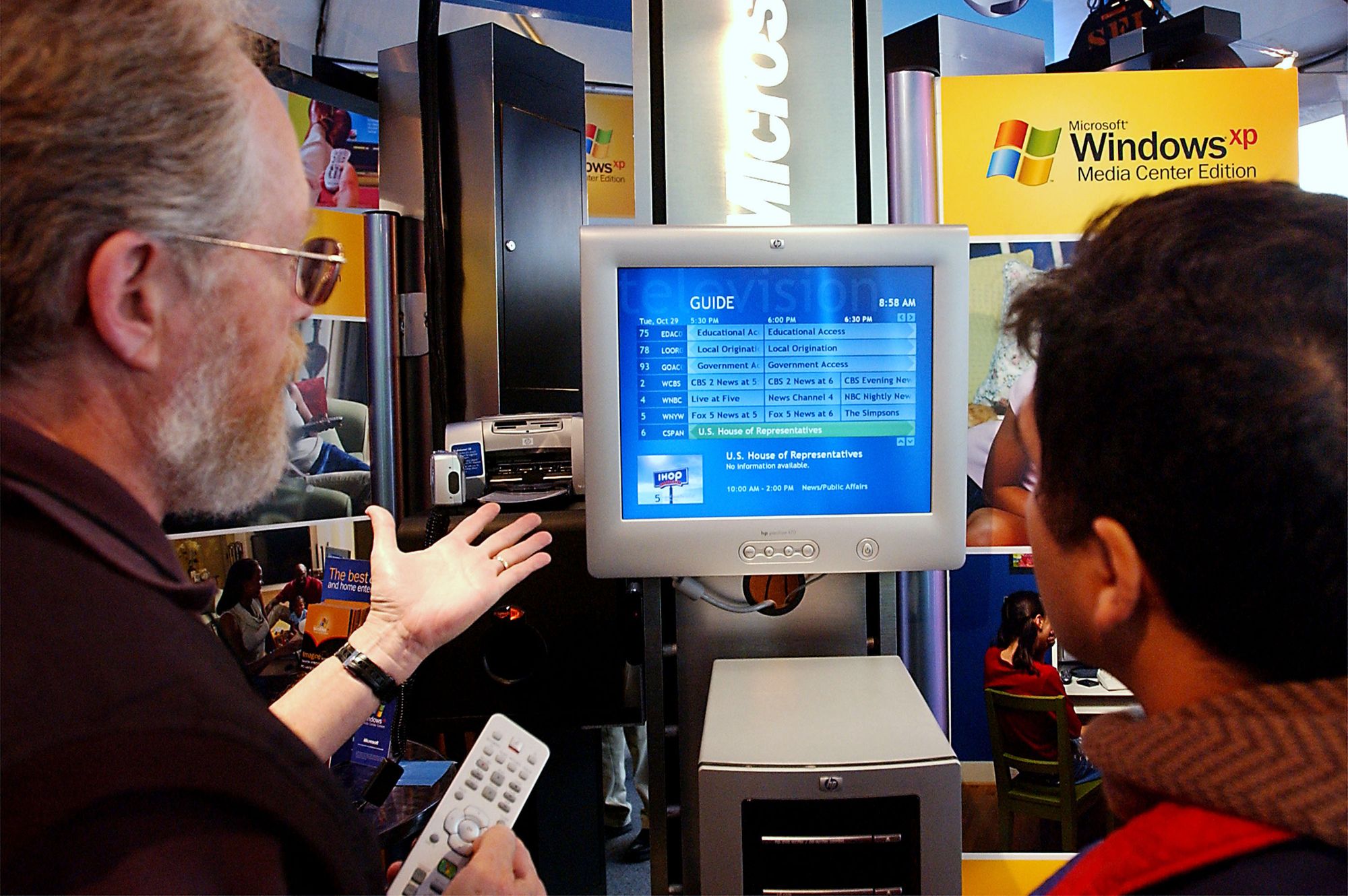

The exceptional reception of the Windows 95, a system which codified such common PC user interface concepts as the Start menu, the taskbar, and an array of window controls, pushed the OS/2 out of consumers’ sight. It did get another major version in 1996 and some feature updates till 2001, but as a desktop environment, the system became irrelevant. IBM ended OS/2’s first-party support in 2006, when the system could only be found as a part of legacy industrial projects.

The end of the OS/2 spelled no demise for IBM—or the Fiesta Bowl, for that matter. Gerstner’s management decisions earned him a reputation as a turnaround artist, with books and studies devoted to describing IBM’s newfound direction. His successor, Samuel Palmisano, completed IBM’s exit from consumer computer market by selling its PC division to Lenovo in 2004. These days, the closest IBM has to a consumer operation is The Weather Company’s web site and apps, which are just a public facet of their B2B forecasting business.

The Fiesta Bowl didn’t have to wait long for good times either. While IBM’s exit made the bowl’s managers to scramble for a just-in-case agreement with the household cleaning company Dial Corp, the final deal was signed with Frito-Lay. The snack behemoth, in a match which arguably made more logical sense than the one with IBM, turned the competition to Tostitos Fiesta Bowl. Promoting tortilla chips turned out to be fruitful for the bowl and its participants, as 1996 payouts were increased from $6 million to $26 million.

Tostitos supported the bowl for 18 years—two more years than the OS/2’s entire development process.

Ernie Smith contributed to research.