Modern phones have long diminished the popular relevance of dedicated point-and-shoot cameras or camcorders: they shoot good enough in most scenarios, are always ready, and, crucially, require no purchase beyond what you paid for the phone. But looking at the same market as it originated 15 to 20 years ago is like looking at this statement in a carnival mirror. Back then, a prospective mobile camera owner had to buy it separately and carry it as an accessory—all for the ability to take photos which, frankly, weren’t very good.

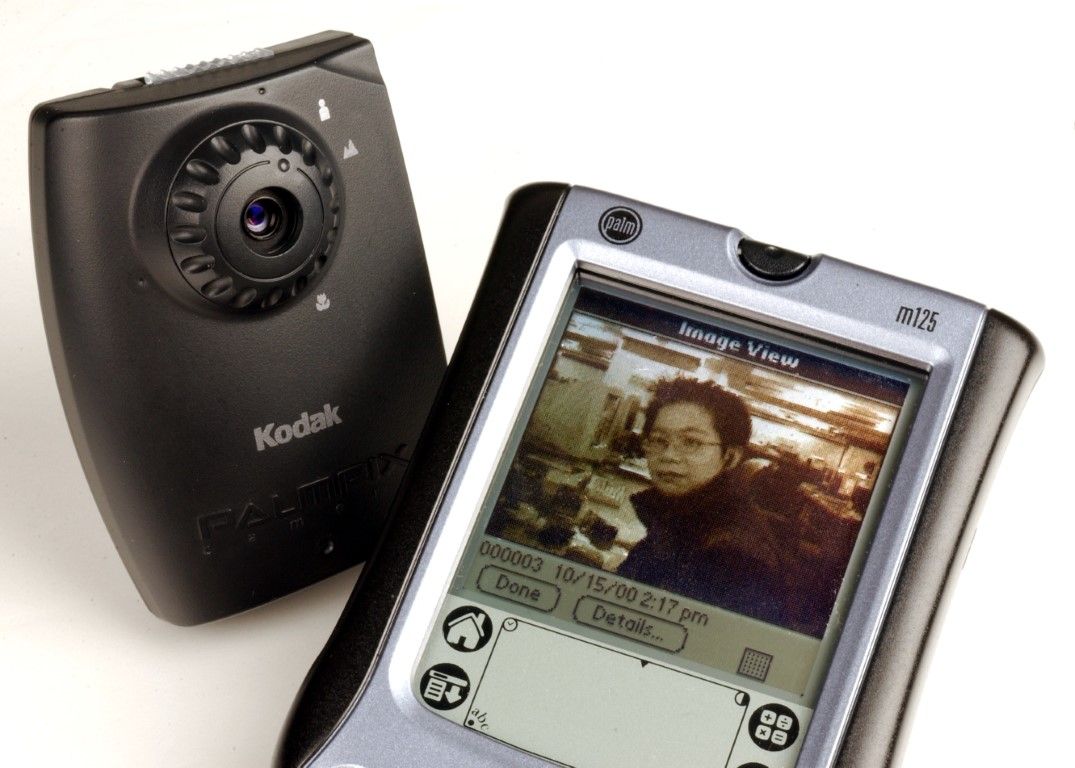

PDAs, short for personal digital assistants, lent themselves to this kind of eccentric expansion. While they were marketed mostly as an advanced alternative to paper organizers, their ability to run third-party programs and connect to hardware peripherals made them appealing to power users on the go. That meant there was an audience with enough purchasing power to release a Palm-powered massager, a $200 Bluetooth module, or, indeed, an early plug-in digital camera.

The age of add-on cameras, whether for PDAs or for other mobile electronics, was short even by the early-2000s standards of fast-paced advancements. Today, 30pin looks back at two such peripherals, released few years apart for competing platforms, to show what preceded the feasibility—both technological and economical—to build camera into devices themselves.

Plenty of PDA accessories had a definite and immediate need to fulfill: you bought a foldable keyboard to type on the go, a wireless modem to check you mail at the airport, and so on. But a fair share of them could be filed under “it’s cool we’re able to fit that into your pocket,” with advertised ways to use not keeping up with what technological abilities yet. Early PDA cameras Eyemodule were not inherently more useful than Nintendo’s less “serious” Game Boy Camera. Sure, the PDA accessory could shot photos which you could send and manage as computer-readable files—just like on the real digital camera!—but it was still closer to a toy than a tool.

Sony, a famed gadget maker, showcased a plug-in camera shortly after they entered the PDA space in 2000. It was made specifically for their Clié series of Palm-powered handhelds which earned themselves a lasting reputation over the next six years, with award-winning industrial design and standout features like high-resolution displays and media playback. Sony’s handhelds pushed the limits of what the Palm OS platform was capable of, so it’s a natural target for some hi-tech accessorizing.

The Memory Stick Camera Module, model PEGA-MSC1, was formally announced in October 2001 and rolled into a “Clié Gear” brand of hardware expansions afterwards. The device plugged into Clié’s Memory Stick slot—the same one which, in its many varieties, was the only way Sony would prefer you to expand your mobile storage for years. Michael Khan, marketing manager for Sony’s digital imaging products unit, told the EMedia Magazine in 2002 that, with Memory Stick, Sony “quickly saw beyond storing data and started looking at interlinking devices.” No devices other than Clié handhelds, however, supported these Memory Stick devices or had their own ones.

The module’s rotating sensor with a fixed-focused lens shot was capable of shooting pictures with a maximum resolution of 320 by 240 pixels—the “perfect size for e-mailing or Web posting,” if we were to believe Sony’s press release. Pictures were stored in a proprietary format within Palm OS-specific database file system but could be exported as JPEG files (confusingly named “DCF” by Sony). Despite the Memory Stick appearance, the Clié accessory had no storage of its own, and the camera application had to be installed using a PC.

Pictures taken with a Clié camera had the same horizontal resolution as a screen of a PDA it was designed to be taken with. However, the app reserved only a stamp-sized rectangle in the middle of a screen to a slowly refreshing preview area. Exporting the image wasn’t snappy, either: it took around 30 seconds to convert a single photo to a standard image file, in 30pin’s testing with Sony’s 2002 entry-level PEG-SJ20 handheld and the original Memory Stick card.

Many reviews of the Memory Stick Camera Module focused on the novelty of taking a photo with a handheld computer rather than on the image quality—and, confusingly, that was true for other similar devices throughout the early 2000s. A brief review in a June 2002 issue of Handheld Computing Magazine stated that the accessory “won’t take the place of any half-decent digital camera.” Rob Pegoraro, the Washington Post tech columnist, was far more critical in his February 2002 review: he said, in a rare passing mention, that “the Memory Stick Camera makes for a better demo than a working product.”

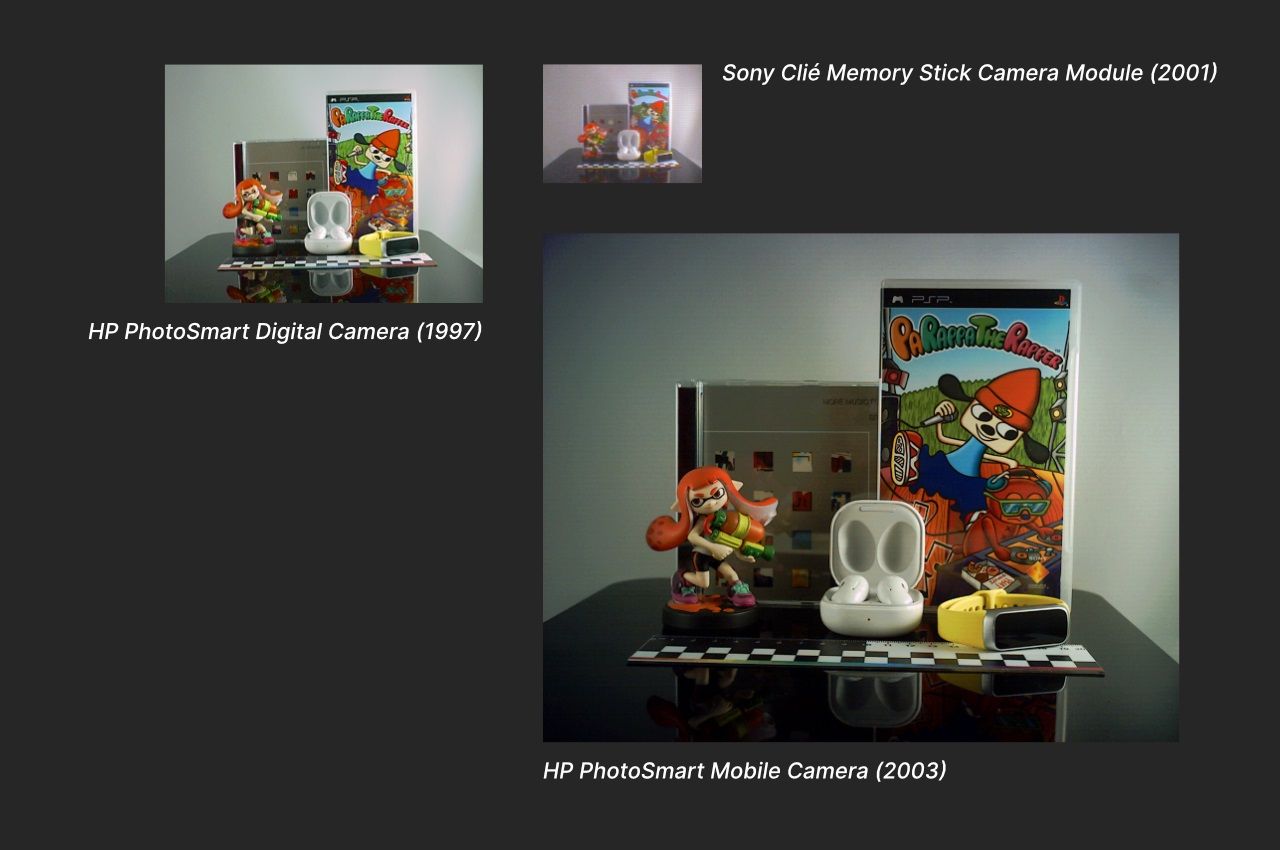

It’s not just the size of images, equivalent to a quarter of a resolution of the most basic 1990s monitor, which hurt their quality. Colors on photos takes with the PEGA-MSC1 look like a crude approximation of what the eye was seeing during the capture. Nothing ever feels in focus, and shooting any full-frame object upfront gives the picture a noticeable fish-eye effect. In a controlled environment, a 1997 HP PhotoSmart digital point-and-shoot camera, functionally identical to an older Konica Q-EZ model, produced a much clearer image—the one where you can actually read the logo on a game box, as seen above. The photo taken with an older standalone camera is also devoid of big multicolored blobs of digital noise, found on any Memory Stick Camera Module photo no matter the lighting conditions.

In Less Than Two Years, a Notable Upgrade in Quality

HP released its first plug-in camera for their Jornada line of Windows-based PDAs in 2001, shortly after Sony’s foray. The camera plugged into a Compact Flash slot, had its own viewfinder and a shutter button, and hit the store shelves before HP’s merger with Compaq and the subsequent takeover of the iPAQ handheld series. This article will cover the module’s effective successor, the HP PhotoSmart Mobile Camera, which used an SD Card standard extension instead.

While the PhotoSmart Mobile Camera matched the silver-painted design of iPAQ handhelds it was marketed with, there wasn’t anything which makes the accessory specific to that particular brand of PDAs. Veo, a California-based company, sold the identical plug-in camera without the HP branding and worked with Palm on making a version of the accessory which would’ve carried the Palm badge instead. (The deal fell through, and Palm carried the Veo-branded version on their store instead.)

HP and Palm announced their variants of the same camera within a month of each other, on August and September 2003, respectively. The PhotoSmart was sold at $129.99, according to online discussions. Veo’s web site was listing the same price, but Palm sold it at their online store for the same $99.95 mentioned in the announcement of the unreleased Palm-branded edition.

It’s not clear whether the sub-$100 price point was something Palm and Veo explicitly agreed on and had to honor later. The manufacturer’s site had drivers for both Pocket PC and Palm OS devices, but the latter ones came with no support and “as a courtesy for Palm users.” Veo did not even mention the Palm OS compatibility on the camera’s product page, further adding to the suggestion it was made for the Microsoft platform first.

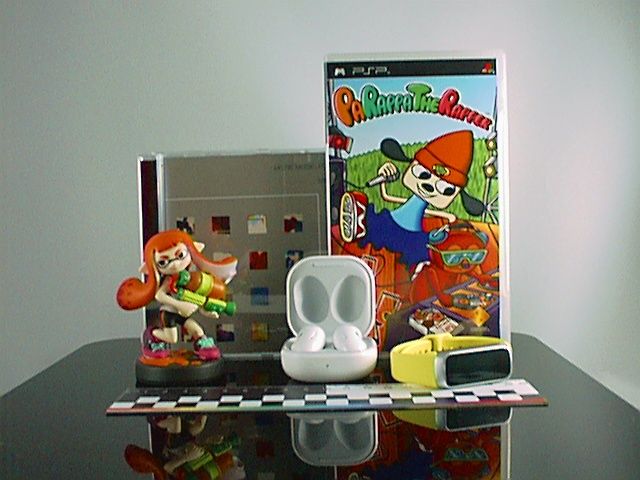

HP PhotoSmart Mobile Camera shared the general way of work with Sony’s accessory: it, too, plugged into a memory card slot and let you take both selfies and scenes facing the user with a rotating lens. Unlike the Memory Stick accessory, it’s considerably bulkier and, in 30pin’s testing, doesn’t lock into the card slot properly. In spite of shortcomings of the industrial design, the camera takes much crisper photos than a Sony one. While it tends to underexpose most of shots and adds an excessive vignetting effect, it doesn’t turn everything it takes into a rainbow mush like the Sony one.

The indoor picture quality of the PhotoSmart Mobile Camera is below the one offered even by cheapest of contemporary digicams, though, and focusing the shot with a bezel around the lens is tricky considering the minuscule preview area. However, under good lighting conditions, the accessory manages to mostly best its 1996 standalone relative, a goal which the Memory Stick camera was far from reaching.

A look beyond enthusiast web sites and consumer electronic press reveals a peculiar strong point of the PhotoSmart camera: the way it could be integrated with third-party applications, thanks to a development kit made public by Veo. Syware, a Massachusetts-based maker of mobile database software, added support for the camera to their flagship Visual CE product in 2004. The camera found an extensive usage in the mid-2000s research on accessibility tech, object and character recognition, foreshadowing applications like Google Goggles and Google Lens. While later iPAQ handheld had built-in cameras, some researchers noted there was no API for them—in layman’s terms, there was no documented way for third-party applications to get data for the camera—and they had to use the plug-in one.

Adding a Camera Versus Adding Another One

PDAs were not the only portable electronics to support camera accessories. Ericsson and Siemens released similar modules for their mobile phones, and Sony’s video gaming unit was introducing various revisions of a PlayStation Portable camera until 2009. But Palms, iPAQs, and similar devices, due to their positioning as literal pocket computers, both asked for cutting-edge expansions and attracted forward-looking users who appreciated them.

A burst of mid-2010s experimentation in mobile tech led to two concepts which companies like LG and Motorola tried to capitalize on: modular phones and 360-degree photography. Both went nowhere by the end of the decade, with a performance of devices like the LG 360 and Hasselblad’s snap-on zoom camera showing that people were largely disinterested in expanding what they had in their pocket. Consumers were showing progressively more interest in phones which were doing less, forming a market for Nokia’s classic phone revivals and designer devices like the Light Phone.

With the opposition to nuance seemingly embedded into any collective online discussion, there is a risk for any odd class of devices to be called failures. But in retrospective, there is a difference between a step in the wrong direction and a step which organically led to the current state of affairs.