In 2009, a Polaroid Sun 600 camera arrived at a college bar in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The camera, age 28, was older than both the bar itself and the person carrying it. It was under the arm of amateur photographer Marita Murphy, who was grabbing some graduation-week drinks with her younger brother and his college friends. Once inside, Murphy set the camera on top of a round table where her brother’s friends could admire it.

Eventually, Murphy elevated the camera and turned it on some of the curious faces at the table. Someone gasped and said, “Wait, you’re actually going to use it now?” And with that, she triggered the shutter, and the camera belched a loud sna’errrrupp. The Polaroid ejected a single, white-bordered photo containing a candid image of the celebrating graduates. It would take a few moments to develop.

More than a decade later, Murphy, 37, works in radio production in San Francisco. As she shared her story with 30pin during an email interview, she recalled that at that moment, the entire bar turned to watch. “It was really the iconic sound of the Polaroid that stopped people mid-conversation and had lots of heads turning,” she remembers.

Murphy was among the last of those able to get their hands on the original film for this vintage camera. Early in 2008, the Polaroid Corporation—or what was left of it—announced it was going to stop producing film. This wasn’t quite accurate, though. It had already stopped.

People’s passion for instant cameras outlived Polaroid’s intention to make film cartridges. But without them, every one of these old cameras would end up in the landfill. Was there any way to bring the camera supplies back?

A Few Millennial Missteps

The Polaroid Corportation’s downhill slide started many years before Murphy inherited the camera. In 1997, its stock had been trading at $60 per share, but by October 10, 2001, it was trading at just 28 cents. The company prepared to file for bankruptcy protection. What happened?

Polaroid had plenty of time to see that digital technology was coming down the pipeline, and in some ways, it acted on this foresight. According to a 2009 article in Yale Insights, a publication from the Yale School of Management, Polaroid was investing heavily in digital photography by the end of the 1980s. A decade later, its digital cameras were among the top of their class in sales.

But Polaroid made several missteps.

First, according to Yale Insights, the company overestimated consumers’ need for a tangible, printed item. Polaroid’s CEO Mac Booth made this clear in a 1985 letter to stockholders. “As electronic imaging becomes more prevalent,” Booth wrote, “there remains a basic human need for a permanent visual record.”

Polaroid echoed this assumption that printing would remain important fifteen years later in a 2000 New York Times article describing this printer-focused strategy. Then-CEO Gary DiCamillo told the Times, “The cameras are just another way of capturing images, many of which we hope people will want to print.” He sounded a bit less certain than Booth had.

Second, a number of Polaroid’s products released around the turn of the millenium either flopped or failed to come to market quickly enough. These included inexpensive kids’ cameras decorated with Barbie and with the Tasmanian Devil; its pocket camera, which took pictures on a self-adhesive strip; its smaller-sized Joycam, which used old film from its failed SLR camera; and its single-use, disposable camera.

Third, Polaroid’s company culture exhibited a distaste for electronics and, later, for anything digital. It was married to its instant film technology, and it was not interested in adding electronic components to its camera technology. This meant that for Polaroid, chemistry was king. Former Polaroid executive Hugh MacKenzie told Yale Insights, "The culture of the leadership was chemistry and [film] media first.”

It was this chemistry that defined the company. DiCamillo told Yale Insights, “Instant film was the core of the financial model of this company. It drove all the economics—not instant cameras and not hardware or any other product; it was instant film.” The film, DiCamillo noted, had a 65 percent gross-profit margin.

Polaroid’s film technology was, indeed, a marvel of chemistry and design. What we call instant film—those thick, white-edged rectangles we load into the camera—is perhaps better described as a film unit. To produce an instant photo, a film unit that includes a film negative, a positive print medium, and, in the middle of this sandwich, a “pod” containing a chemical developer reagent, is rolled out of the camera. The rollers crush the pod and release the developer reagent. This is what allows a photograph to develop instantly, without use of a dark room.

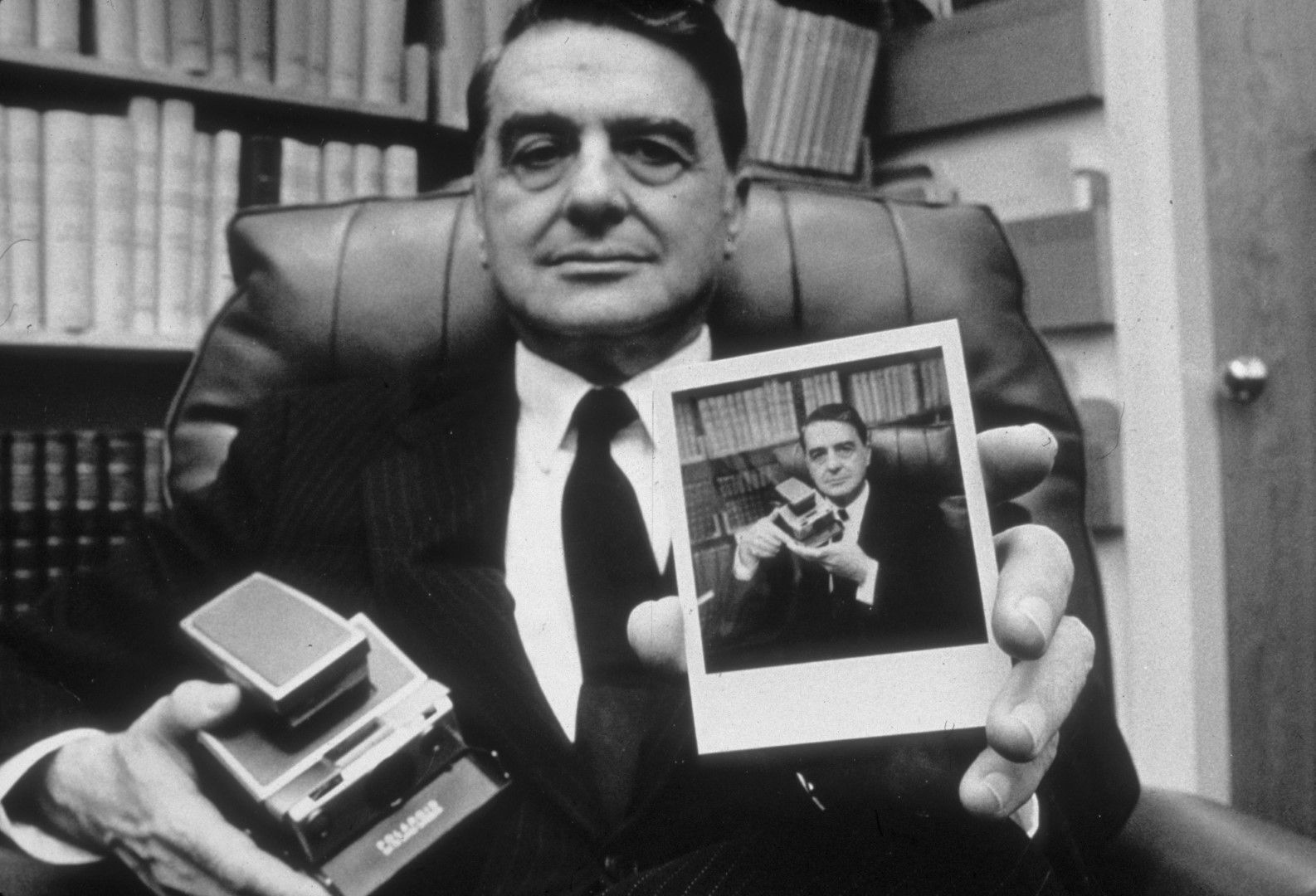

The first version of the instant camera was developed in 1947 by entrepreneur and charismatic Polaroid founder Edwin Land. In 1972, Time Magazine’s cover story was about Polaroid’s new user-friendly SX-70. It was titled, “A Genius and His Magic Camera.” While instant photography was dismissed by some cultural critics as a gimmick, photography magazines such as The Camera and American Photography; artists including Andy Warhol and Ansel Adams; and consumer public welcomed the new product.

Yet despite having invented these magic pods, it didn’t look like the Polaroid Corporation would survive another decade. As digital cameras became more popular, film and film camera sales continued to plunge. Polaroid was delisted from the New York Stock Exchange, and by 2001, retirees were left with a depleted pension fund and now-worthless stock they’d been in many cases forced to buy. It seemed that a digital image, easily shared, edited, and stored, was the way of the future.

Polaroid changed hands several times after 2001. In 2005, Petters Group Worldwide, busted during the Great Recession for being a Ponzi scheme, bought the company and created a 5-year plan for it based on a “forecast” of the rate at which demand for film would taper off. First, the company would produce all the film this forecast predicted it could sell over 5 years. Then, film sales would support a business model based on putting the Polaroid brand name on objects mostly made overseas, such as LED picture frames. Finally, the instant-photography branch of the company would quietly fade away.

The Impression That Never Faded

But that’s not what happened, though, according to David Hale, Polaroid’s Vice President and head of American Sales who worked for the company for three decades until 2008. In an interview in the 2012 documentary Time Zero: The Last Year of Polaroid Film, Hale explains that Polaroid film consumers kept buying film at a steady rate, not a decreasing rate. By 2008, supply stockpiles were running out well ahead of schedule. On top of this, Polaroid’s film-making factories had been long shuttered, and the bulk of its workforce laid off.

Far from this crumbling empire, at the beginning of 2009, Murphy was clicking through eBay listings in an increasingly difficult mission to find affordable film for her new camera. She had been given the camera by a friend who was excited to have found someone who might use it.

The film Murphy had that day at the bar was original polaroid film, expired, and the photos weren’t quite as sharp as she had hoped. Still, she explained, her Polaroid had stood out from the crowd of digital cameras. It had made an impression, and not just on her brother’s friends, but on all the people who turned to watch the Polaroid at work in the bar that day.

But casual interest from a bar crowd wasn’t what precipitated Polaroid’s turning point. Instead, some of the many enthusiasts appalled by the 2008 announcement that film production would cease formed a group called The Impossible Project. It’s mission? To resurrect an abandoned Polaroid factory in the Netherlands and recreate Polaroid film. A website for a 2020 film called The Impossible Project calls Polaroid enthusiasts “the analogue heroes who dare to swim against the digital tide.”

The Impossible Project was aptly named. An instant film unit must contain every chemical needed for image development. According to the Time Zero documentary, some of those chemicals (such as mercury) had been restricted since the pods were first designed. Plus, old manufacturing processes, which had taken a long time to perfect, would be almost impossible to recreate in the resurrected factory.

Still, The Impossible Project pressed on, with the help of 14 former Polaroid employees. In early 2009, a Facebook group named after The Impossible Project was created in support of the endeavor. By later that year, the group boasted a membership of 3,700. (That number is at nearly 13,000 today).

While Polaroid enthusiasts were working to save analog photography, amateur Polaroid photographers continued buying Polaroid cameras. They found working cameras at yard sales and thrift stores, and in the forgotten corners of attics. And once in hand, these photographers would seek out film, creating ample demand.

Senna Flora, 32, a Tucson-based educator and artist, told 30pin during an interview that “it’s about the novelty.” She uses a 600-series camera she found in an outdoor free-box to photograph friends and family. She likes to give the photos away as gifts. The film is a bit expensive for her. She can only buy one 8-pack a few times a year. But, she said, it’s worth it.

Alana Cox, 30, a small business owner in Brooklyn, has been buying film since before the shortage. She told 30pin in a phone interview that she had “never connected with any Polaroid people online,” meaning that she’d never joined a group of Polaroid enthusiasts. However, she has maintained an interest in Polaroid photography since high school, when she started picking up cameras from yard sales.

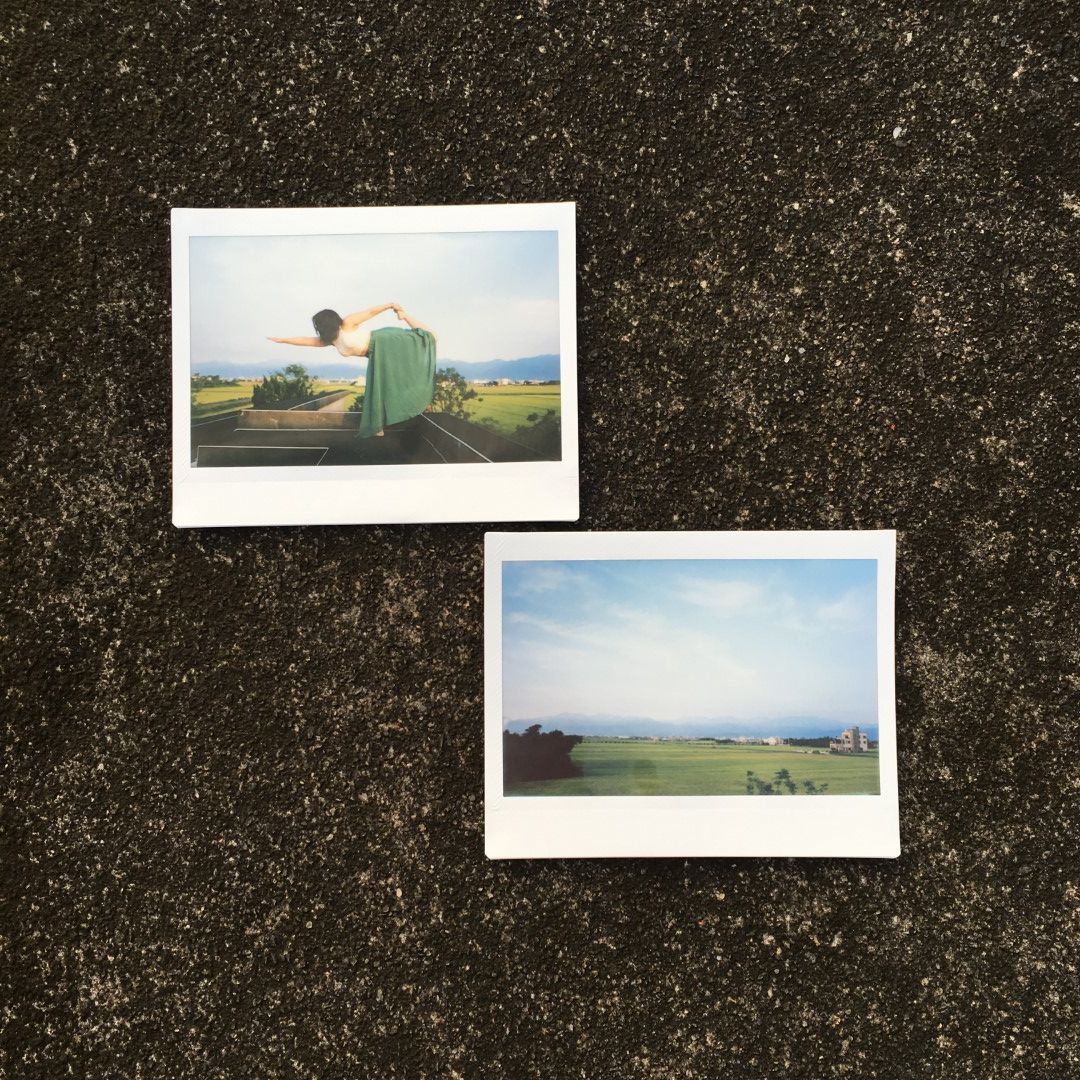

“I do love the Polaroid die-hards,” she said, but she herself isn’t too particular about the brand-name of the equipment. For her, it’s about the photos. Instant photography isn’t about having just any kind of printed photograph. It’s about creating “a true, physical, ineditable, moment in time,” she said. She also likes not having to work in a dark room or fiddle with Instagram filters for hours. “With a Polaroid, there’s so much chance to it. It’s up to the Polaroid gods how it turns out,” she said.

Imperfection in the Digital World

If, at the turn of the millennium, Polaroid made the mistake of leaning too much on film and chemistry, in 2008, it was this analog, single use film unit and its fans that had the power to save the company.

The Impossible Project successfully produced its first film at the Netherlands factory in 2010, just before it would have run out of start-up funds. It has continued selling instant film and growing as a business since then. While users on Facebook complain that first-generation film from the Impossible Project doesn’t work all that well, newer generations offer higher (if sometimes uneven) quality and good variety.

In 2017, The Impossible Project bought the rights to the Polaroid brand, and changed its name first to Polaroid Originals, and then just Polaroid. It started producing a new generation of cameras, including the Polaroid OneStep and the Polaroid Now, to rival the Fuji Instax. It also sells all sorts of printers, from ones that fit in your pocket to large format printers; accessories, such as apparel, camera bags, and filter lenses; new digital and hybrid cameras; and a variety of vintage Polaroid cameras with film to fit.

Twenty years ago, it seemed that the brewing obsolescence of chemistry and tangibility—the very things Polaroid stood for—would spell the end of instant photography. Yet now, adrift in a digital world, we seem to long for a reason to look away from the screen, to share something one-of-a-kind with friends, to take a break from filtered and edited perfection. Instant film offers just that.

Edited by Yuri Litvinenko.

Correction, September 28, 2020: A previous version of the caption under Cox’s selection of photos mislabeled them as Polaroid shots. They were actually done with a modern Fuji Instax camera.