If we chronicled every move Microsoft has made to capture markets beyond general computing, the record would span 30 years of one-offs, obscurities, and commercial flops. While the company did secure its position in the gaming market with the Xbox, its other home appliances and personal gadgets were far less successful.

Microsoft can’t be blamed for not trying hard enough, though—at least, if we are talking about the sheer variety of approaches. They tried both following the leader and coming up with novel concepts; collaborating with household brands or dismissing them aggressively; acquiring companies or licensing technologies to them.

One of the things Microsoft had to offer to gadget makers was an operating system which, at a glance, closely resembled their most famous creation: Windows. In the late 1990s, the four-color flag, already synonymous with PCs by that point, appeared on the predecessors of modern phones and tablets. That system continued to be in use decades after its first release, but with none the public recognition Microsoft was once pushing for. What happened?

“Why Are We Doing This?”

If memories of going shopping for groceries aren’t completely forgotten in this lockdown-induced haze, you might recall the industrial-looking interface of a cashier’s terminal, or a barcode scanner mounted in the aisles. And at many points on their way to the store—or your home, if we are talking about deliveries—those products were scanned using a clunky, sometimes gun-shaped mobile computer.

Chances are high that all of these devices, no matter if they were made five or fifteen years ago, are running Windows CE, a low-profile system licensed to embedded hardware manufacturers. It was developed in parallel to the desktop Windows, rather than being derived from it as the name suggests.

Since the mid-1990s, PC manufacturers licensing Windows have been barred from modifying its interface or hiding defining features like the Start menu. In contrast, Windows CE licensors are allowed to pick and choose what they need from the system and put their own user interface over it. That renders the system featureless by design.

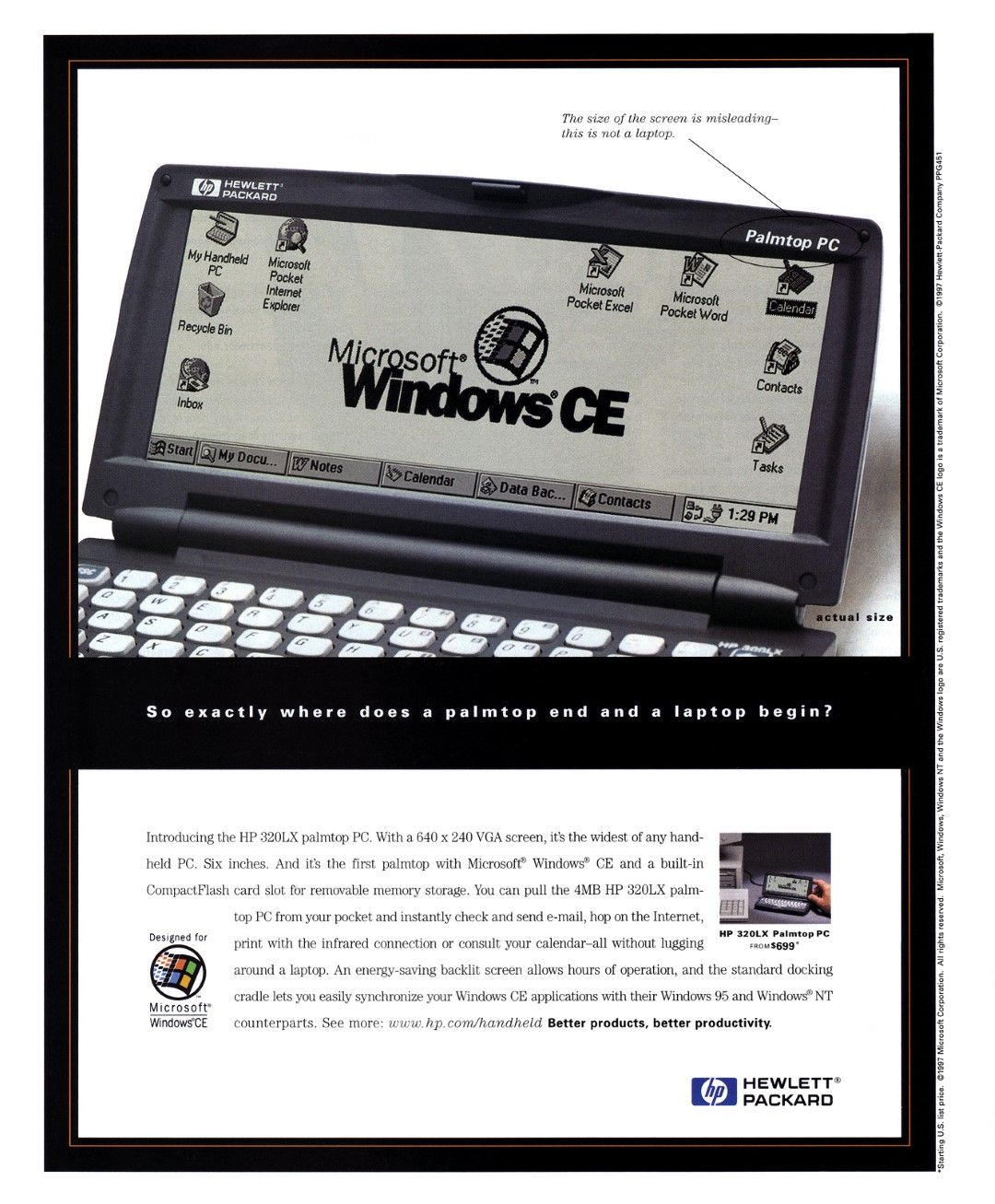

This approach differs from the way Microsoft treated Windows CE in its early years. Most Windows CE devices had the system’s logo “emblazoned right on the plastic case,” Fortune reported in 1998, noting that “Microsoft wants consumers and businesses to think of Windows as ubiquitous—not just a figment of the PC screen.” While the system could be licensed by hardware companies only, Microsoft was running magazine ads for it, promising that Windows CE-powered handheld computers were like “having the essence of your PC at your fingertips.”

To push the adoption of Windows CE, Microsoft brought their main asset into action: a Windows 95 user interface, fresh off a reported $300 million marketing campaign. While Windows CE did not sport an exact copy of the desktop’s interface, there were enough elements of it, from icons and taskbar buttons to the bezel-rich nature of each interface element, to evoke familiarity. With the initial batch of Windows CE devices, the effect was highlighted by the hardware design: so-called “Handheld PCs” were designed to look like miniaturized copies of contemporary notebook computers.

The idea of an ultraportable computer aiming for continuity with a desktop was novel. Every other mobile computing platform of its time, from Apple’s intelligent notebook to General Magic’s collection of “virtual rooms,” was rejecting associations with desktop computing as much as they could. The idea behind Windows CE was to “prevent users from having to learn a completely new paradigm,” explained Sarah Zuberec, Microsoft’s User Research Manager, in Eric Bergman’s Information Appliances and Beyond. (Zuberec was researching and overseeing Microsoft’s mobile platforms from 1994 to 2005.)

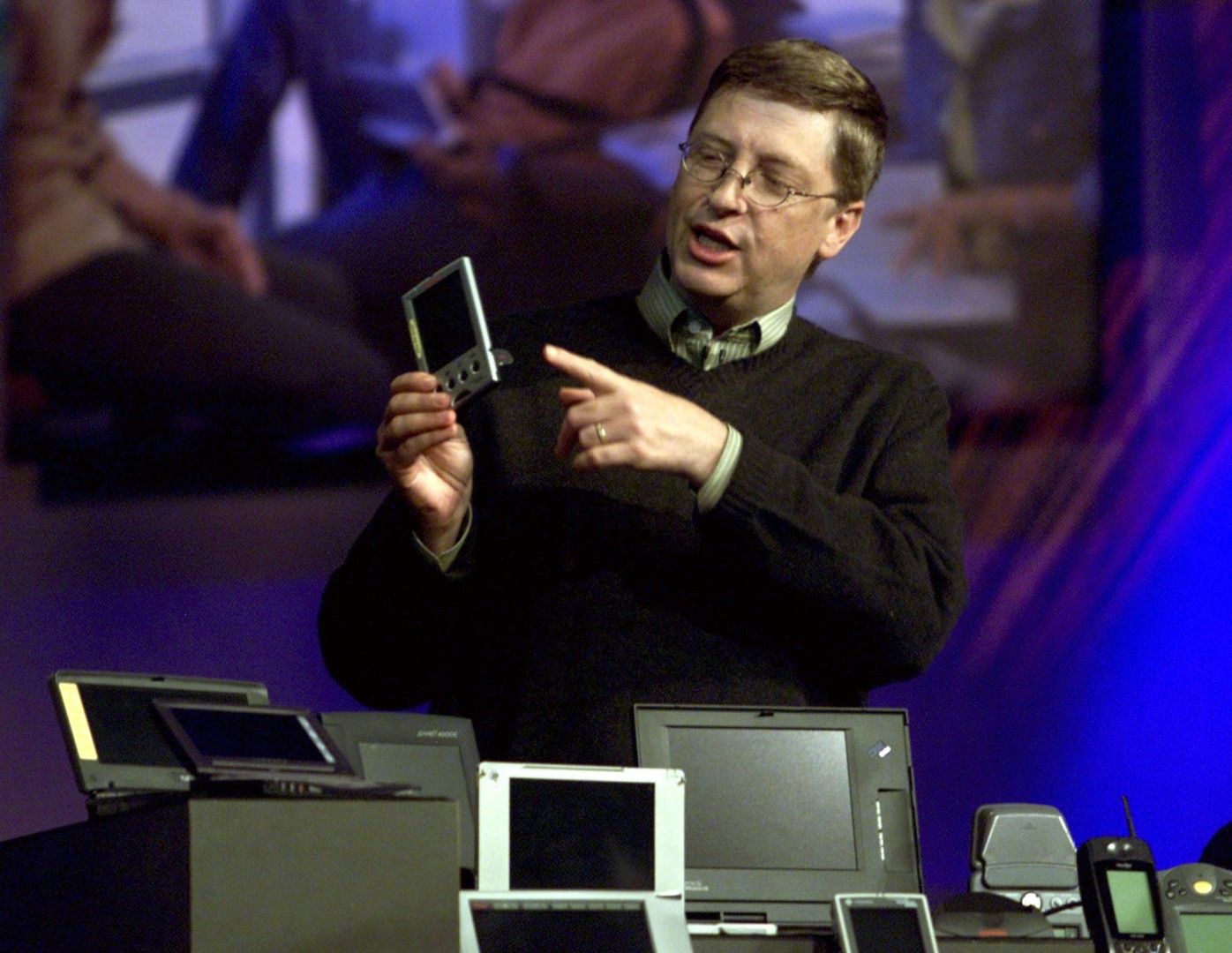

Windows CE was Microsoft’s third attempt to make a dedicated mobile computing platform, and the first one which reached the market. Before that, the company had been simultaneously working on two other projects, codenamed WinPad and Pulsar. Both concepts were previewed in 1993 by Bill Gates, Microsoft’s co-founder and then-chairman, with the work on the former beginning a year prior.

The WinPad was a part of the “Microsoft At Work” architecture which aimed to provide a unified way for office equipment to talk to each other. The main focus of the platform was to let PCs send documents to printers and faxes and get data back from them—say, a real-time printout status. But the wider concept also included portable devices and networked landline phones. “The idea is wherever there is a screen… you are to be able to call up the directory and see who’s who and get the information about them,” young Gates is seen promising in archival footage published by Microsoft’s Channel 9. (Microsoft shut down the blog after this article’s publication, but the video file was still left on their servers.)

“Microsoft At Work for Handhelds,” which WinPad was called in the media, was based on the same instruction set as Windows 3.1, a 16-bit operating environment and a predecessor of modern Windows versions. Its later editions, meant for software developers who tested prospective platforms, were found alongside pre-release versions of 32-bit Windows 95. Both systems were designed for ordinary PCs, and the WinPad device had to be a PC as well—not a trivial task at the time when notebooks were just starting to be reasonably-sized. The software project was built around a chip set made by Intel and VLSI, codenamed “Polar,” which was supposed to replicate the desktop 80386 processor in a low-power package. The joint hardware project was canned before any WinPad device came close to being shipped.

While WinPad and the At Work initiative were created for Microsoft’s business clientele, the Pulsar project was meant to have mass appeal. Gates publicized the so-called “wallet PC” concept, describing a small portable computer which would replace IDs and credit cards with messaging and organizer capabilities, in 1993. Nathan Myhrvold, founder of Microsoft’s Research division had pitched him the concept in 1991. “There is no reason why you can’t just carry a single little PC about the size of a wallet—a little flat-screen device that has all your authentication credentials,” as Gates explained in his speech at the University of Washington (as quoted in The Seattle Times).

Pulsar was the first attempt at implementing Gates’ vision of a wallet PC, said Harel Kodesh, Microsoft’s former VP of Consumer Appliances, in an email interview with 30pin. “It didn’t look like Windows; it didn’t share the same API as [the 16-bit] Windows… The team had a feeling something big was happening.”

Gates described the wallet PC numerous times, referring to it as a vision of the not-so-distant future rather than a project in development. Gates’ 1995 bestseller The Road Ahead (which Myhrvold co-authored) laid out one of the most detailed descriptions of the wallet PC. Today, this account reads like an eerily accurate description of a modern phone, made long before even basic cell phones were commonplace. “Your wallet will link into a store’s computer to allow money to be transferred without any physical exchange at a cash register,” said Gates in a passage which would fit modern tap-to-pay systems like Apple Pay. At a later point, he imagines a wallet PC user asking the device for directions to the nearest Chinese restaurant, just like one would ask Google today.

Microsoft was not working on Pulsar by the time The Road Ahead hit store shelves. WinPad was no longer in development either, as both teams were reorganized in 1994. In John Murray’s Inside Microsoft Windows CE, Robert O’Hara, a WinPad development lead, said Gates was disappointed with the lack of shared direction. “I’ve got WinPad and Pulsar working on handheld computing, doing two completely different things. Why are we doing that?” he said, quoting Gates.

Brad Silverberg, Microsoft’s Senior VP of Personal Systems, was tasked with building a single team. “Neither [project] to me seemed like it was on a path to success, though each had some good ideas,” recalls Silverberg, famous for shipping Windows 95, in an email interview with 30pin. To him, Pulsar was “a long way from being a product.” (Murray’s book quotes more direct criticism of the project, with Silverberg reportedly blaming the Pulsar team for not doing the market research and comparing their creation to a student project.) However, he appointed Kodesh, who oversaw Pulsar, as a leader of the merged team. “I chose Harel and a number of WinPad people left the project, which is understandable in these situations,” Silberberg says.

“Fortunately, the Products Sucked”

The principal hardware design was one of the first things agreed on, as requested by Microsoft’s existing partners. “In 1994, HP and Compaq started to ask us to build a professional device,” Kodesh recalls. The former had already been making their “palmtop PC” mini-notebooks, and the new handheld PCs inherited the same clamshell design. “The form factor was considered a winner among knowledge workers who wanted a keyboard and ability to type fast.”

Before the team settled on a desktop interface, the new system “did not have the affinity necessary to identify itself as a Microsoft Windows product,” wrote Zuberec. User interface prototypes published in Information Appliances and Beyond show the main menu with a grid of icons and a bar of ever-present, silk-screened buttons. (On many touchscreen devices of that era, the touch panel was bigger than the LCD display behind it. Silk-screen printing was used to add buttons and control elements to the extra touch-sensitive space.)

The team originally wanted to build the user interface around the concept of documents. The goal of the prototype, according to Zuberec, was to test whether a user would see it as a container for documents or as an application shortcut. Initial experiments, though, revealed that users were split on how to treat the interface. Zuberec attributed the split to the fact the test group was made up of “early Windows 95 users”—that system, as well as every other Windows after it, supported both paradigms.

According to Inside Microsoft Windows CE, the Windows 95-like user interface, which Zuberec quoted as being adopted after feedback from “top-level marketing and executive staff,” was prototyped over a weekend by Tony Kitowicz, the project’s shell lead. “It was all from scratch, brand new,” the book quotes him. Kitowicz felt it was a compliment when people viewed Windows CE as a port of the desktop system.

The first batch of Windows CE devices was released in the United States in October 1996. By that time, the mobile computing market was upended by Palm, then a subsidiary of U.S. Robotics, and their Pilot “connected organizers.” Palm averted the need for a keyboard by using “Graffiti,” a stroke-by-stroke handwriting recognition system. Instead of trying (and failing, due to 1990s tech limitations) to decipher a person's real handwriting, Graffiti made them learn a simplified alphabet where every letter was written in a single stroke. This not only made the text input reliable, but also allowed Palm to build a compact, candybar sized device with a big touch screen—not dissimilar to modern phones.

Palm was aware of the resources Microsoft was putting into Windows CE. Ed Colligan, former VP of Marketing who later became Palm’s president, was quoted in Andrea Butter’s and David Pogue’s Piloting Palm, “We were thinking, ‘Geez, how are we going to compete with this?’ Fortunately, the products sucked beyond our wildest dreams.”

The contrast between Windows CE’s desktop-like appearance and the limitations of the platform made things worse, argued Conrad Blickenstorfer, co-founder of Pen Computing Magazine, in a personal interview in 2018. (He reaffirmed his stance to 30pin before the publication.) “No windows, no cascading, no resizing, no minimizing, no mouse support… All this only added to the frustration of ‘seeing Windows,’ but really only having a tiny and very slow part of it.”

By the end of the year, only NEC and Casio shipped their Windows CE devices, accounting for a bit more than 3% of a market share combined (according to the Dataquest report quoted in a Harvard Business School case study). Meanwhile, Palm shipped more than 360,000 units, capturing more than a half of the market after making it 2.6 times bigger almost all on its own.

Computers, Consoles, Car Stereos…

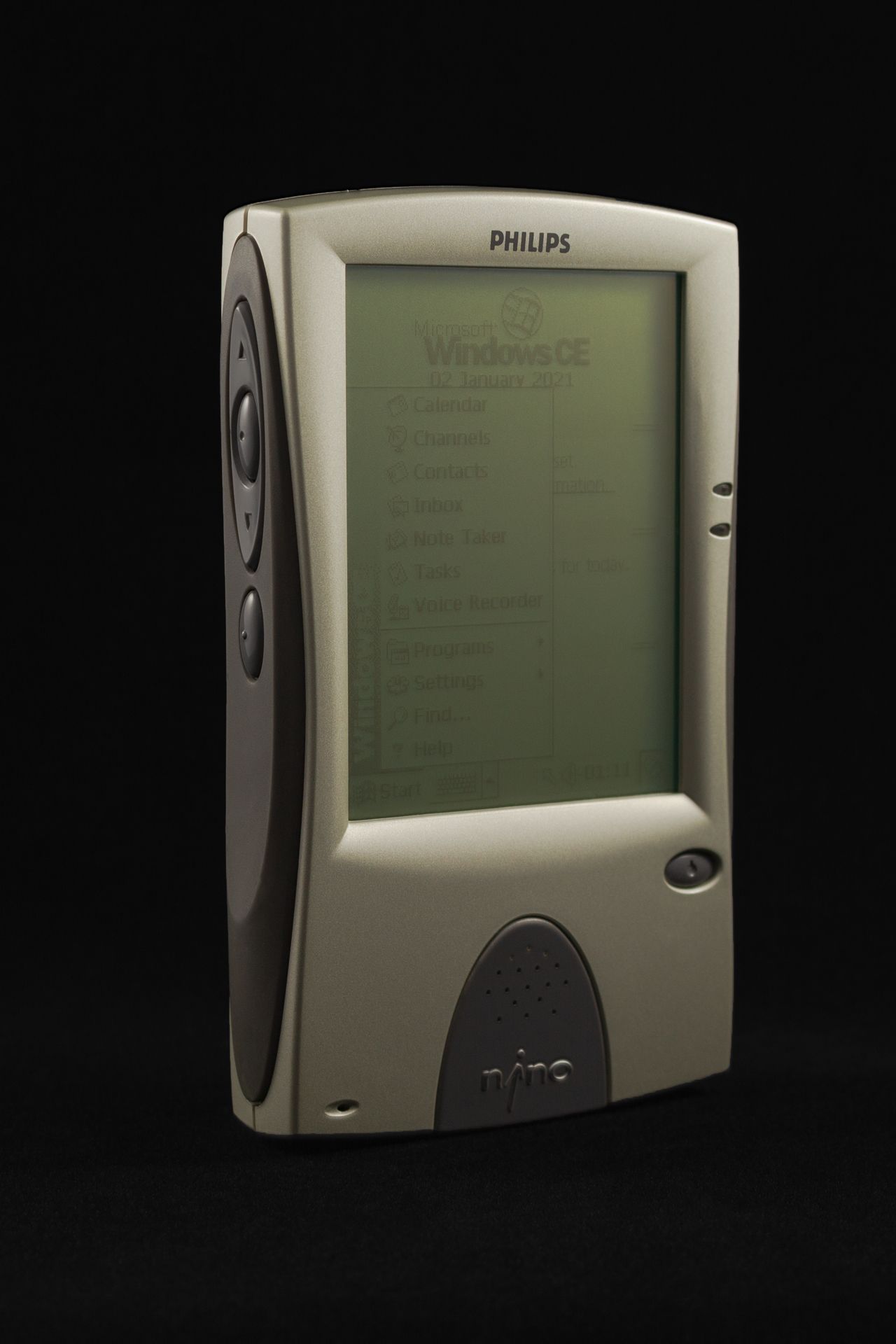

The next version of Windows CE, released a year later, added support for color screens, improved synchronization with PCs, and added new “pocket” versions of Microsoft’s desktop apps. It also served as a basis for Microsoft to counter the threat of being outperformed by Palm. In 1998, an amount of hardware form factors on which Windows CE was allowed to run expanded notably. Among them was a “Palm PC” (renamed to “Palm-size PC” after a lawsuit from 3Com, Palm’s new parent company), a hardware design with neither keyboard nor a clamshell case.

The demand for a Palm-like device, according to Kodesh, was expressed by original equipment manufacturers, hardware companies working with Microsoft. “OEMs started to ask us for a portrait, smaller form factor, probably because of Palm. And they thought, as well as we, that relationship to Windows would be an asset, so we continued what we did with H/PC.” The team tweaked the Windows CE interface to fit the smaller screen but preserved the resemblance to a desktop system. Even the taskbar was kept, although, at 240 pixels wide, it barely fit the Start button and a notification area.

The first time Microsoft moved away from mimicking ordinary Windows was when they had to put Windows CE into a car. The “Auto PC,” unveiled the same day as Palm PC, was aimed at combining the best of late 1990s in-vehicle infotainment, such as CD playback and turn-by-turn navigation, with voice commands, hands-free calling, and connectivity with Windows CE handhelds. Most powerful Auto PCs, such as the $3,000 Clarion Joyride, used desktop-class processors to display maps and play DVDs and MP3s.

“In the car, driving is the primary task. Any interaction with the Auto PC while driving is considered a secondary task, and input and output methods were designed with this in mind,” wrote Zuberec. While top-of-the-line systems had their own large screens, the base hardware (like the first Clarion AutoPC, with a suggested retail price of $1,299) had to rely on a screen smaller than a single-DIN faceplate. “Viewing angle and distance defined the font size. Hardware that fit into the standard car stereo slot allowed very few hardware controls.” And yet, some Windows iconography was preserved, including a hardware Start button.

A less obscure example of putting a Windows CE logo on a device outside the realm of computing was the Dreamcast, Sega’s last video game console. Under a deal with Sega, Microsoft adopted Windows CE for the console while Sega declared the compatibility on the front of its case. The collaboration was meant to allow developers to “create cross-platform titles more efficiently” by using the same tools and instruction sets to make games for both Windows and Dreamcast. It wasn’t quite the same promise Microsoft would make later with its own Xbox, but the direction was similar.

Microsoft’s instruction sets and libraries, used in Windows CE for Dreamcast, were intended to ease the cross-platform game development. Developers are still using similar “middleware,” albeit without a full-fledged operating system tacked on, with its licensing often requiring developers to disclose the use of the technology in a game’s splash screen or credits. But the terms of the agreement between Sega and Microsoft yielded the latter a level of publicity unprecedented even today. The Windows CE logo was not only put on Dreamcast’s case, but within a startup screen for every game which relied on it.

Most games didn’t. Of 600-plus games officially made for Dreamcast, only 78 used Microsoft’s game development option. The others were made using Sega’s homegrown tools. Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six, ported to the Dreamcast in May 2000, missed the console’s launch because of a “lack of experience” by the porting team and “issues surrounding the use of Windows CE,” CNET reported. Besides, the Dreamcast itself did not have Windows CE built in: it had to be kept on and loaded from the same one-gigabyte optical disc as the game itself. Developers had to account for this overhead in storage and performance, too, as Windows CE itself was using a bit of console’s resources.

“Dilutive to Microsoft”

Shortly after its launch, Windows CE went from supporting a single, strictly defined type of device to powering a whole range of devices, mostly incompatible with each other on both software and hardware levels. That range, put into a single picture, would’ve impressed any manager focused on scale and corporate unity the same way as Google’s homogeneous corporate-colored app icons would today. But within Microsoft, there was an attempt to rethink the expansive strategy and revert Windows CE to its original form.

The 2001 book Breaking Windows by David Bank describes the “Starting from Scratch” memo, sent by Kodesh to Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer. The Windows CE lead proposed to leave the original system for use with handheld PCs only, kill off its other flavors, and then create a division within Microsoft which would have worked with hardware vendors to create a tailor-made embedded software—namely, the one for cell phones. Gates rejected the idea.

“I was losing the war there,” tells Kodesh 30pin. “We have not moved enough from Windows—that was both an asset and the liability.” He argues that people like the Windows experience because they know how to operate within it, but it didn’t allow Microsoft’s mobile team to simplify it further. According to Kodesh, if he wouldn’t leave the company in 2000, his next battle would have been “diverging from the Windows interface.”

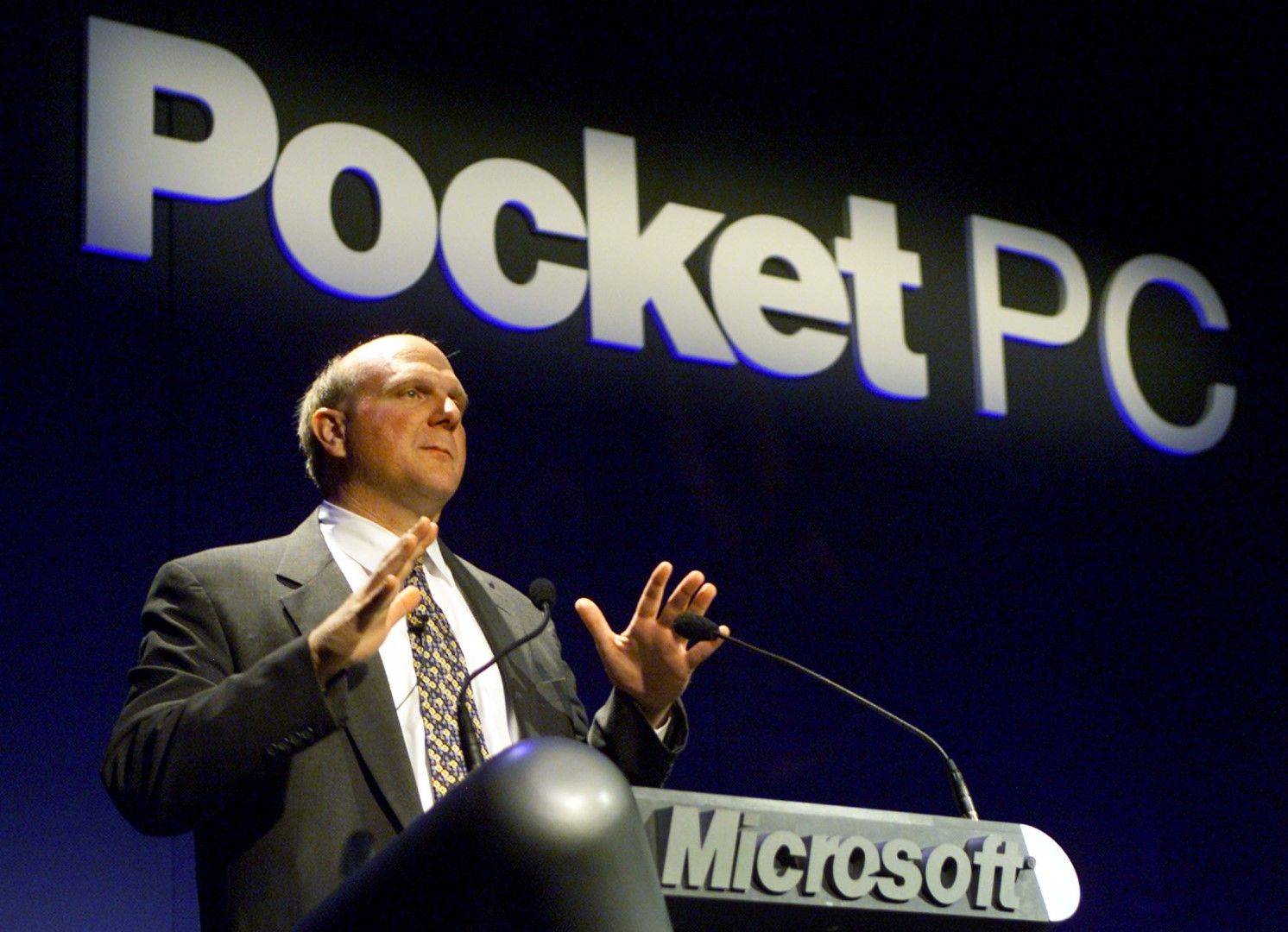

Before leaving the company, Kodesh shipped a revamped version of a palm-size PC platform. Dubbed “Pocket PC,” the new software was stripped off several desktop interface concepts which didn’t make sense either on small screens (like the taskbar) or, in retrospect, on any device which would fit into a pocket (double-tap to activate icons). The system’s appearance was streamlined as well, with bezels gone and toolbar icons flattened. The system kept being visually inspired by Windows, but the sense of squeezing as many desktop elements as possible into a 3.5-inch screen was not as pronounced as before.

The release of the Pocket PC in April 2000 also marked the moment Microsoft started to move the Windows CE brand away from the consumer spotlight. The platform, as well as its Handheld PC 2000 relative and a later Smartphone 2002 spin-off, continued to be based on Windows CE. But in the software branding “Windows” was now a descriptor, not a centerpiece, as the device were released with a mouthful of a full name: the Microsoft Windows Powered Pocket PC.

The sidelining of the Windows CE brand was explained to the developers a week after the launch of the Pocket PC. It was a part of a wider reorganizing within Microsoft, with divisions responsible for the Windows CE and embedded versions of the desktop Windows combined under the helm of Bill Veghte. A new brand, “Windows Powered,” was meant, per Microsoft’s press release, to “simplify and unify all the Microsoft embedded and appliance solutions.”

Microsoft’s executives “were convinced that Windows should grow up, not down,” said Kodesh, recalling the pressure from Microsoft’s corporate marketing. “There was a concern that the Windows CE is dilutive to Microsoft.” He points at the feedback from salespeople who “started to complain they are trying to sell laptops, but people want the lighter, thinner, instant-on devices”—just like notebook-sized “Handheld PCs Pro” made by Windows CE licensors.

“Windows CE never had a chance because Microsoft made sure to keep it nearly useless, so as to not compete with Windows,” argued Blickenstorfer. To him, Microsoft was never committed to pen-based computing “because all [it] was ever interested in was the desktop and laptop version of Windows.”

The Windows brand wouldn’t return to the company’s mobile efforts in earnest until 2005, when the Pocket PC and the Smartphone platforms were partially unified as “Windows Mobile.” The Windows Powered name remained an obscurity, most prominently seen in custom, enterprise-ready installations of the Windows 2000. As for a new interface which wouldn’t rely on familiar Windows concepts, that took another five years, a new generation of mobile platform, and the release of the Windows Phone 7.

“That Thing Called CE”

The shift in the way Microsoft handled the Windows CE was seen not only in marketing. After the Handheld PC 2000, the company stopped providing hardware manufacturers with the original version of the system. The Auto PC platform did not get a new standard user interface either, with later automotive applications of the Windows CE being mostly stripped of their Microsoft identity. (Some versions of the Blue&Me infotainment system, used in cars by pre-merger Fiat Chrysler Automobiles well into 2010s, had a Windows key on a steering wheel, though.) Microsoft did make a new Windows CE platform for portable media players, but it was discontinued after Microsoft decided to compete with Apple’s iPod on its own.

“Microsoft were always chasing what made the most commercial sense. They experimented with different form factors and ultimately chose the same path as everyone else,” writes Chris Tilley, editor-in-chief of HPC:Factor, a site that has served as a community hub for handheld PC users for the last 20 years. In an email to 30pin, he argues that Microsoft should have followed with focusing on the clamshell design. “The H/PC was—and in fact to many still is—a viable productivity tool,” he notes, describing tiny Windows CE-powered notebooks as “creation devices” as opposed to “consumption devices.”

Tilley thinks the era of Windows CE 2.0 represented the age of experimentation at Microsoft. “No one knew what ‘the’ form factor was going to be,” he said speaking of a flurry of hardware variations supported by the system in the late 1990s. However, Tilley notes that said variety, combined with constant changes in the core system and the high cost of development tools, “fractured the developer ecosystem.” “Microsoft had this thing called ‘CE’ but didn’t really know what to do with it,” Tilley says. “They came up with the technology and then attempted to find a use for it.”

The year 2012 marked the end of Windows CE as a system Microsoft itself would want to build consumer products with. The Windows Phone 8 got the same kernel as the desktop Windows. The move brought the system closer to the vision unveiled alongside the first edition of Windows 10 in 2014: the one of a single system, used on everything from phones and PCs to consoles and Internet of Things devices.

With Windows 10, Microsoft offered developers the way to write a program which, if they would like to, would run on all types of devices supported by the system. The vision lost some of its charm after the phone version of Windows 10 was abandoned after years of irrelevance. However, Microsoft was successful in porting the desktop version to ARM processors, foreshadowing Apple’s move to its own chips with the same architecture. The company has also released a stripped-down version of Windows 10 for embedded devices, complete with a migration plan for clients who still hold onto Windows CE.

In the late 1990s, Microsoft was bringing its secondary system to various hardware platforms; by the 2020s, its flagship software product received the same treatment. But with the upcoming Windows 10X, there is a new set of risks for the company. The streamlined edition of Windows was supposed to run exclusively on dual-screen devices but was later confirmed to power single-screen PCs as well. Alongside with differences in programming instructions and the app support, there is a chance Microsoft would once again create a similar-yet-different system.

With Windows 10X and the future of Windows as a whole, Microsoft faces a different challenge than 25 years prior. But as a precaution, it’s better for everyone to look at the system which ended up in a less prominent position that was once envisioned.

Edited by Samantha Lomb. Special thanks to Ernie Smith for getting a copy of Inside Microsoft Windows CE on behalf of 30pin.

Correction, February 10, 2021: Due to a technical error, a paragraph in the closing section of the article was published alongside its draft version. We’ve removed the latter.

Update, February 1, 2022: A dead link to the Channel 9 video was fixed.